I have been working on my spiritual memoir entitled, Spirit Lifting, for the past few years.

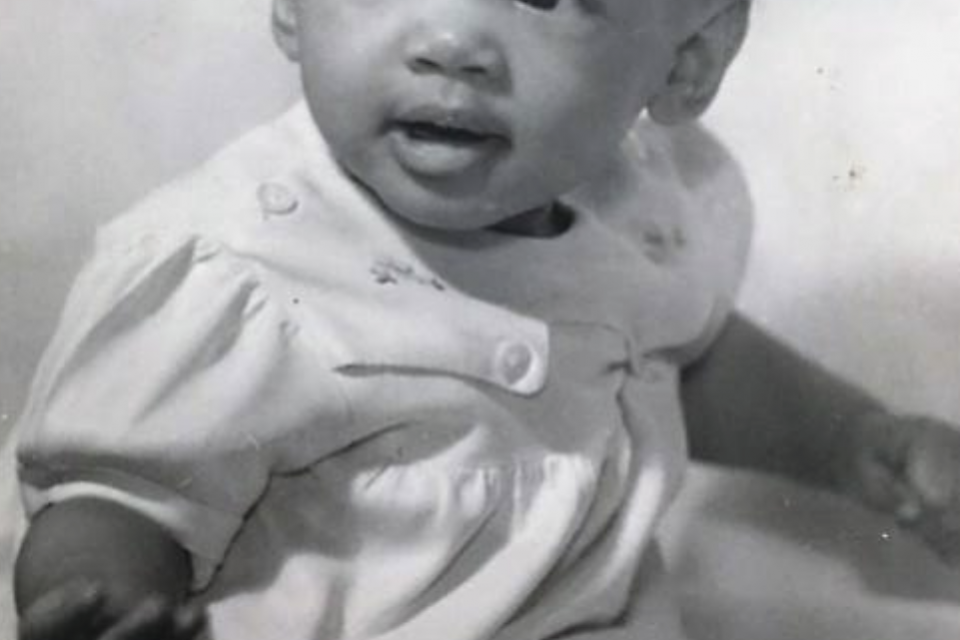

Here’s the Prologue, with a pic of me as a baby! (A sample chapter follows.)

PROLOGUE

April 8, 1981 – Pittsburgh, PA

I stepped off the visitor’s elevator at St. Margaret’s Hospital in Pittsburgh, PA, and made my way past the nurses’ station, maneuvered my way past the lunch carts stacked with half-eaten trays and wandered through the corridors, until I located the semi-private room assigned to my great-aunt, Rebecca Gross. As I entered the room, I noticed the second bed was empty. I welcomed the privacy and was glad I would not have to pull the curtain or listen to some elderly patient’s moans.

I was the firstborn girl in my family of six children, and thus became my great-aunt’s favorite. She loved and doted on me from the beginning, unabashedly playing favorites between me and my siblings. I would sometimes feel bad about this, but realized her behavior was beyond my control. Besides, she gave me lots of nice gifts.

Aunt Rebecca was a constant figure in our house; she was part of all of our major as well as minor events. Growing up, my sister Gwen and I regularly spent time at her compact apartment, which was located on the third floor of one of my parents’ homes in the Homewood section of the city. We often spent the night with her. During her later years, my aunt lived in my parents’ home in Stanton Heights, also located in a section of Pittsburgh. She was there when my daughter, Tara, was born in 1972.

My aunt was prone to moodswings—if she liked you, she liked you. If she didn’t, you’d better watch out, for she liked a good fight, whether her own or someone else’s. She didn’t take anything from anyone; she was an “in your face” type of person. She liked TV wrestling—Ingomar Johanssen and Bruno San Martino were her favorites. Her other likes included beer, Luden’s cough drops, Hawaiian Punch and chicken. (She raised chickens in the city and would wring their necks to kill them.)

Aunt Rebecca liked to read tea leaves and coffee grinds, and she was pretty accurate with her readings, too, I’m told. Part African-American and part Cherokee Indian, she also belonged to the esoteric Eastern Star Society. My aunt would terrorize us sometimes with ghost stories and stories of the devil, and she always kept a wooden board slanted at the bottom of her stairs to ward off evil spirits.

As kids, whenever we stayed overnight at her home, one of our jobs right before we went to bed was to make sure the wooden board was down and slanted in the right position—and you’d better believe we always did this job correctly—as who needed disembodied spirits chasing them through the night! We sometimes slacked on our other jobs, though, such as cleaning, and got hit with a wet stinging dishrag or a thin switch from the tree as our punishment. But life was more good than bad with Aunt Rebecca, for she was truly a great aunt and we loved her, as she did us.

What mostly came to mind for me this particular morning was the description that my aunt used to give us, of how “Death” would visit each and every one of us one day, and how he would patiently lie in wait to slowly pull the cord that would end our lives. A very poignant thought, for on this particular day, my aunt was 92 years-old and lay dying.

She was a waif of a woman now, gaunt and skeletal with sunken cheekbones, her Cherokee lineage quite evident. Today she looked nothing like the stout, robust, feisty, outspoken woman I knew and loved all my life; it was so sad to see her this way. I knew for a while that she was ill and hospitalized, but I just couldn’t bring myself to visit her in such a deteriorated state; not until this particular morning, that is. Somehow I knew without being told that today would be her last day on this earthly plane, and I knew she was waiting for me to come so we could say our honored and fated farewells to each other.

I timidly approached the metal hospital bed, leaned down, and planted a warm kiss on her cool forehead.

“Hi, Aunt Rebecca,” I said softly. I’m here.”

She appeared not to hear me; her eyes were glazed and focused on something or someone off in the distance. But after a short while, she brought her full attention towards me. Her eyes were grey and watery. For several minutes, we imploringly looked at one another, neither of us speaking. I thought she was incapable of speaking at this point, but after a brief while, she opened her mouth and began to half-whisper to me.

“I need to tell you something,” she began.

“Ma’am?” I asked hesitantly.

“Me, Peter and my brothers…we killed our father.”

For a moment, nothing seemed to register as I peered at her through my glasses. “Ma’am?” I repeated again, clearly shaken.

“We killed him, our father. We hung him.” she continued.

Grimacing, I immediately thought this has to be some kind of sick joke. But under the circumstances, I understood it couldn’t be, because dying people don’t tell sick jokes, or any other kind of jokes, for that matter. Furtively seeking some kind of rhyme or reason to this, I remembered that my great-aunt had slowly been going senile these past few months.

After all, she was ninety-two. Some days I would speak to her by phone, and she would be coherent, carrying on long, intelligent conversations, and other times she would lapse into speaking nonsense. She would sometimes catch herself and say, “Don’t mind me, I’m just talking out of my head.” Then she would give a little, short, embarrassed laugh, and I’d produce a weak smile on the other side of the phone, feeling sad at what was befalling her. I understood her undoing was beyond her control.

This was clearly not how I had envisioned our last day together to be. I really hadn’t envisioned this day at all, to be honest; but, had I envisioned it, it would not have been like this. Nevertheless, out of reverence for her as she lay dying, I hesitated to interrupt her, so I let her continue…

“We all vowed to take this secret to the grave with us, but I’m the last one alive.”

I still didn’t know what to think or say—so I simply nodded my head, and like an imbecile said, “Yes, ma’am,” again.

“I used to tell you he was mean and would beat my mother (which she had said many a time in the past), and when he would be around his White friends drinking, he’d say, “Them niggers ain’t mine!” referring to me and Peter (Peter was her brother, my late beloved grandfather). We hated him, so we hung him,” she said matter-of-factly, as her voice trailed off. She then became quiet, as did I.

I sat on a small, uncomfortable chair placed next to the bed, uncomfortably lost in thought. This was frightening and unsettling, even if it was senility talking. After some time, I noticed that my aunt’s breathing had become more labored. I reached for her hand to comfort her, and was suddenly struck by how cold and clammy her hand felt. Startled, I said a quick prayer and arose to hit the emergency button.

A young nurse appeared. She looked at my aunt, took her vitals, and adjusted the IV before scrawling figures hurriedly on her chart. She evasively answered my questions, but I could tell by her furrowed expression as she left the room, things weren’t good.

Shortly thereafter, I heard the click of heels and shuffling feet approach and cautiously enter the room. Glancing up, I could see it was my parents and younger sister, Debbie, arriving. The mood was solemn as they bent to kiss Aunt Rebecca, straighten her bedcovers, and search for seats. They had stopped at the nurses’ station beforehand, and had been given a more clear and dire prognosis than had been offered me. The slight commotion seemed to elicit no response from my still aunt whose eyes were open but vapid at this point.

Before long, we began to hear what is referred to as “the death rattle” rising up from my aunt’s throat. (A ghastly, gurgling sound some people make shortly before they die.) It was quite frightening to hear; it eerily did sound as though Death was pulling a cord and strangling the life force out of her.

This went on for quite a while, though the nurse made my aunt as comfortable as possible. Eventually, my aunt succumbed and took her last weak breath. She was a good fighter, but of course she always knew this was one fight she wouldn’t win. This was my first experience witnessing an actual death. It was apparent to me the moment my aunt’s soul left her body, as I was able to clearly see it leave.

At the same time, the light in her eyes simply went out, as though a light switch had been flipped; all animation disappeared. I don’t remember the exact cause of death. I know my aunt suffered from diabetes, but at ninety-two years-old, it could be said she simply died of old age.

I did not speak of what my aunt told me to anyone that day or for many years to come; I merely dismissed it as the ramblings of senility. Besides, the implications were too horrendous for me to deal with. For, at that time, I was only in my twenties—a time to laugh, have fun and party.

I tucked it all in the back of my mind. There would be plenty of time to make sense of this when I got older.

0 comments on “My Memoir”Add yours →